As I sit and write this it is hot! Unusually for the UK, it has been hot for weeks, and the heatwave is only set to continue. Luckily, I live by the coast and when I’m not at home writing blogs about food, you can almost certainly find me at the beach swimming in the sea.

Lately this hasn’t been without its risk, as seas around Britain's coastline have become plagued by Jellyfish. Ok, so it’s not much of a risk, as most of them are pretty harmless, with stings not as bad as a nettle, but a risk all the same.

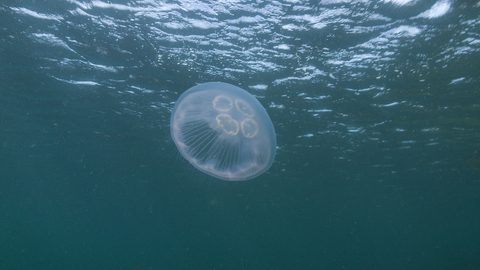

As I was swimming along the other day, thinking about the rising cost of food and how we are going to sustainably feed a growing global population, I noticed a little blob of jelly bobbing about in the clear, warm water ahead of me. It was a moon jelly. One of the most common jellyfish in the world.

Once I had swerved out of reach of one of the little blighters, I noticed another, and another. Then I saw a whole smack of moon jellyfish, all bobbing along together (yes, smack is the collective noun for jellyfish. Cool huh!?). Obviously my next thought was ‘can I eat these, and if so, could they be the answer to the global food crisis we’ve all been looking for?’

It seems that the number of jellyfish in the world's oceans is on the rise, with many more reported ‘blooms’ globally each year. This could be down to the rising sea temperatures, increasing the population of phytoplankton (their food), and increasing their growing speed. Another factor could be the overfishing of predator species and competitors, giving the jellies more of a chance to thrive. Of course it could just be that, since the 1990’s, more and more scientists have been looking into jellyfish, and therefore reporting more blooms.

In reality, a combination of these and many other factors are probably the cause of any jellyfish population spikes, which, apart from making my daily dip a little more exciting, could cause untold damage to the marine ecosystem and beyond.

For one thing, jellyfish don’t have many calories. This means that, although they are predated by many a sea creature, it is rarely their main source of energy. More of a snack to get them through to lunch. With more jellyfish and fewer actual fish in our seas, animals such as whales, dolphins and sharks simply aren’t getting the calories they need to sustain them.

Also, by eating up all the phytoplankton, the Jellyfish are depriving many creatures of their main food source. Both of these factors and others, have a myriad of knock on effects that could potentially be disastrous to all marine life.

So, should we stop catching cod and tuna and turn our nets to jellyfish instead. It seems that we’re pretty good at reducing the population of marine life by fishing for it, so if the amount of them in our sea is too high, then perhaps eating them is the way to go as a viable alternative protein source.

Although low in calories, Jellyfish are high in protein, as well as antioxidants such as selenium (good for your immune system) and collagen, which is good for blood-pressure, bones and joints and apparently making you look younger. They also contain other minerals too, such as choline which helps your liver and brain function (great for a pub quiz).

Of the thousands of species of jellyfish world wide, only eleven have been found to be edible (one of which is the moon jelly I spotted on my swim), and even then they take a lot of preparation before they can be served up.

If you were to go down to your local beach with a net and scoop out a nice moon jelly, you would first have to cut the bell end from the dangly bits, before scraping away the gonads and mucus.

I know, that sounds 50 shades of wrong, but that is honestly what you have to do! Fishermen across Asia, where jellyfish have been eaten regularly for nearly 2,000 years, are cutting the dangly bits from their bell ends everyday.

Once you’ve discarded the dangly bits, it is important to quickly salt the jellyfish. Traditionally, in Southern China this is done in a ceramic vat where the jellyfish are stored for about a year. Commercially this is often done using a combination of salt and Alum (Potash or Potassium Aluminium Sulphate). This reduces the pH level and firms up the texture. Bicarb can sometimes be added for the same reason.

The salt draws out some moisture and turns to brine. This brine is washed away and the process is repeated for three to six weeks, until the jelly is creamy white and firm. Once dried it can be stored in airtight containers for a long time, although it may turn yellow as it ages. If it goes brown, then it is gone off, and not safe to eat.

Another technique I have come across (thanks to the Facebook group Costal Foragers UK) is to submerge the jellyfish in ethanol (96% proof) for a few days. The alcohol replaces the water content of the jellyfish, before evaporating away, leaving a small, crisp disk. Apparently it doesn’t taste of much, but the texture that has been described as ‘an idiosyncratic mouth feel’.

Luckily, you won’t have to do any of this processing as many Chinese and Asian supermarkets stock dried Jellyfish, or it can be bought online relatively cheaply. A quick google found it available on Amazon for under £5 for 170g. It is recommended that the dried jellyfish is soaked overnight to reduce its salty flavour and improve its texture. It is then usually shredded and served in a salad or as sushi. It isn’t cooked though, as apparently this turns it to salt water.

The flavour of Jellyfish has been described as somewhere between oyster and jellied eel, with a surprisingly crunchy, slightly chewy texture, rather like slightly over cooked calamari. If you’re a Asian seafood lover, then this recipe, kindly supplied by Shu Manni, Moderator of ‘Chinese Cooking’ Facebook group, is definitely one to try.

Thanks for that - an interesting and enjoyable post. I'm all up for eating renewable resources like this. I doubt that I could be bothered to identify, catch and prep my own jellyfish, but I have just searched for dried ones!